A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention – Herbert Simon, Nobel Laureate. Let’s be honest, we’re pretty lucky as jazz musicians in this day and age. As a musician interested in jazz today, you have access to more recordings and resources related to learning this music than any previous generation of improvisers struggling to learn how to play over chord changes.

This is the age of information after all. By clicking a button, you can look up virtually anything you desire to know. With sites like Wikipedia, YouTube, Google Books, and countless other resources, you have thousands of years of knowledge at your fingertips. The only thing slowing you down on your path to infinite knowledge is the speed of your internet connection.

For musicians, the resources available online are vast: you can download virtually any recording or song that you want, you can watch videos of the masters, past and present, on YouTube, you can look up chord progressions in countless fakebooks, you can read interviews with notable musicians… You can even watch live performances online from New York jazz clubs like Smalls and hear archived shows of some the best players in the world.

But, is this overabundance information really helping us improve as improvisers?

Too much of a good thing

As it turns out, instant access to a plethora of information can be both a blessing and a curse. With a computer we have access to limitless information, but since it’s so readily available, what’s the incentive to absorb it? What’s the point of memorizing anything or taking the time to actually learn it when you can get the answer in seconds from the web?

Because these sources are easy to access, actually acquiring the knowledge for yourself losses its appeal. It comes down to simple economics really – anything in great supply inevitably goes down in value. With so many records and books in our collections, we become blasé about the value of this information that’s in our possession.

Bootleg recordings and rare concert videos that were once nearly impossible to find (like the tape of Clifford Brown practicing) can now be found in seconds online. They’re so easy to find that we barely have the interest or attention span to listen to them all the way through!

The effect of information overload

This overabundance of information and lack of incentive doesn’t only apply to musical learning. Information on nearly every subject is available online. For example, instead of truly understanding chemistry or mathematics, you can download formulas, tables, and equations as a short cut. You can look up the basic information, but knowing why it’s essential or how to apply it can’t be downloaded in seconds from a computer. That part actually takes time and the determination to work things out for yourself.

This is where we go wrong in our attempts to learn improvisation.

By the time I was in high school, I had more records than I could possibly listen to, dozens of play-a-longs, books of jazz theory and transcribed solos, DVDs of classic concerts…you get the point. Instead of studying what was right in front of me, I searched for more recordings and instructional books that had the secret to improvising effortlessly. The problem wasn’t the quality of information, rather the sheer amount of information and the lack of focus it created.

However, it wasn’t always like this.

In interviews of great musicians of the past, you hear a common theme about how they found records and started learning the music. Most go like this: ‘We would go to the record store, buy one record (that’s all we could find or afford) and go home and spend hours and hours with it. We would learn every tune, every solo, until we knew that record inside and out.”

For the masters of the past, every record was like a treasure. It wasn’t effortless to acquire these records and once you had them, you learned every tune, every solo, every nuance on that album. Looking at recordings in this way, the information on them becomes very valuable. Because these records and resources on learning jazz were scarce, you worked with what you had and you studied the hell out of it.

Pick one album

All you truly need is one great record. Try this exercise. For the next couple of months (or two), pick one record from your collection and focus on it exclusively. Imagine that you are on a desert island and this record is the only one that you’ve got.

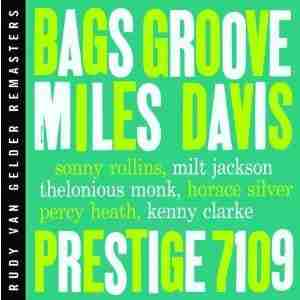

Looking at my own collection, I would probably pick the album Bag’s Groove with Miles, Sonny Rollins, Monk, Horace Silver, Milt Jackson, Percy Heath, and Kenny Clarke.

Check out the tunes on this album:

- Bag’s Groove

- Airegin

- Oleo

- But Not For Me

- Doxy

Every tune on this album is a gem. On just this one album, you have blues, rhythm changes, minor ii-Vs, descending ii-Vs, some standards, etc. If you spend the time and learned all five tunes on this record, inside and out, you’ll have a great start to building a useful repertoire of tunes.

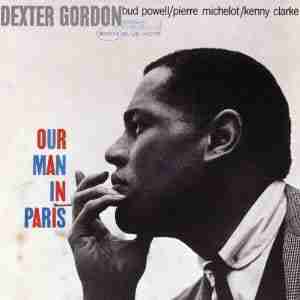

Maybe you’re really digging Dexter’s approach. Pick up the album Our Man In Paris.

On this record you have:

- Scrapple from the Apple

- Willow Weep for Me

- Broadway

- Stairway to the Stars

- A Night in Tunisa

- Our Love is Here to Stay

- Like Someone in Love

Again, all of these tunes are standards that you should know and will benefit from learning. By studying this one record intently, you’ll learn much more than glossing over fifty records.

The list could go on and on. The important point is to pick a record that you love, one that really speaks to the improviser that you want to become. As you work on each tune, transcribe a chorus of a solo or even an entire solo to ingrain the changes and pick up some language along the way.

If you want to take it a step further, spend some more time to learn one or more of the tunes in all 12 keys. Take Scrapple from the Apple:

Once you have it down in the original key. start taking the tune around the cycle slowly, one key at a time. If you’re having trouble with this, put the song into Transcribe to slow it down and change the key of the tune. This way you’ll be able to hear and play-along with the record in the new key.

When you approach learning like this, you could spend years on just one record. Remember that one solo has enough language in it to transform your playing. Even learning one ii-V will put you on the right track to becoming the player that you want to be. Instead of buying more records, put the time in with one album and you’ll see some immediate results.

Less is more

Too much information can not only overwhelm someone learning, it makes the actual information seem less valuable. It’s true that today we have more resources at our disposal in our journey to develop as improvisers, but the key is to pay attention to and study the information that we have right in front of us.

These records really are treasures and if we treat them as such, we’ll learn so much more. Take a look at your record collection right now. You probably have enough material there to study for hundreds of years. Don’t buy another record or play-a-long book, searching for that missing link to success. The answer is probably sitting right there on your shelf. You know, the one that says Bluenote on the cover. Now go put it on and get to work.