Each day when you get your instrument out of its case and set out to practice improvisation, your goal is to play the right notes. Whether it’s playing with great technique and great sound or finding the best line to play over that new tune, you’re looking for the fastest way to sound good over all those chords that you stumble upon. Lucky for us, the right notes have been laid out for us in theory books and on the pages of play-a-long tracks. But have you ever stopped to ask yourself: “Why exactly are those notes the “right notes?”

What is it that makes them right and the other notes wrong? Are we just following the rules of music theory on blind faith or are those “right notes” right because we hear them that way?

Music theory is important in understanding the inner workings of harmony, but the true test of the “right notes”comes with your ear. What does it sound like? The interesting aspect of music is that this “sound” is different for every person. Listening is a truly subjective endeavor. What one person hears as pleasing, another person can find unlistenable, even unbearable.

Sometimes it has to do with personal taste, but more often not it has to do with exposure and experience. I remember the first time I listened to Schoenberg’s Pirot Lunaire:

To my untrained ear, it sounded overly dissonant, almost like noise. However, putting it on today it sounds surprisingly accessible. The piece of music is exactly the same, but the listening, performing, and other musical experiences that I’ve had in the intervening years have changed my ears. My definition of dissonance has evolved, my ears have changed.

You’ve probably had the same experience listening to recordings or checking out players that you were unfamiliar with. On that first listen you unconsciously make judgements based on your musical experience and the styles and harmonies that you’re familiar with. Your perception of “great improvising” evolves the more you learn and the more you listen, over time your ear slowly changes.

The same should be true of the way you hear melody and harmony. Your conception of the “right notes” should evolve and expand the more you are exposed to musically. But sadly, this is not always the case. A large number of improvisers are stuck clinging to the rules of harmony that they dutifully memorized as a beginner.

Year after year, improvisation remains addled with strict rules that are cast in black and white, right notes vs. wrong notes. You become boxed in to this rigid mentality and as a result, every solo starts sounding the same.

Don’t be limited by the rules of music theory

It would be a shame if you limited yourself to the bare basics of music theory when you improvise: Ionian over Major chords, Dorian over minor chords, and Mixolydian over V7. This is a good place to start building your harmonic foundation, but it’s going to get boring and predictable if left undeveloped. Musical interest at its most basic level comes from tension and release, the opposition of consonance and dissonance.

Think of harmony like a painter’s palatte, an expressive collection of color with limitless variations and options. You don’t have to paint only in primary colors or relegate your thinking to black and white. There are infinite shades and nuances to explore, there are varying levels of harmonic dissonance and consonance that can be applied to each musical situation depending on how you feel at that moment.

Just as you had to learn the sound of the root, the 3rd, the 5th, and the 7th of a chord, you need to familiarize your ear with the other notes: the 4th, the 6th, the 9th and even non-diatonic notes like the #11, the #5, the #9, and so on. These notes aren’t wrong, they are just a different color, a different source of harmonic tension that you can use in your lines.

“To study music, we must learn the rules. To create music, we must forget them.”~Nadia Boulanger

Try to get away from the mentality of right and wrong when it comes to harmony and think in terms of different colors or shades of sound. Every note is fair game when it come to improvising over a chord and the only limiting factor or “rule” is the sophistication of your ear.

The reason that some notes sound wrong is simply because your ears are not accustomed to them. You need to acclimate your ear, you need to expand your options beyond the basic chord tones. The good news is that this transformation doesn’t require a huge undertaking. With some focused practice on a few key exercises, you can spend a few minutes in the practice room every day and completely expand your harmonic conception.

Below we’ll take some notes that are commonly looked at as “wrong” or avoid notes and figure out how to make them a useful part of our harmonic palatte by changing the way we hear them.

The 4th scale degree

The 4th scale degree is commonly looked as an avoid note on Major and V7 chords. Don’t sustain it, don’t play it on a strong beat, and never ever start a line with it. It clashes with the third, arguably the most important note of the chord. Because of this, many improvisers avoid this note altogether, playing it safe and sticking the chord tones.

But, this doesn’t mean that you have to leave this note out altogether or only use it sparingly as a passing tone. With a little practice the 4th can become a useful part of your playing.

The first step to mastery with any scale, chord tone, chord progression, transcribed line or musical technique begins with getting the sound of it in your ear. If you can truly hear it, chances are you’re going to be exponentially more successful at playing it on your instrument.

Approach each of these “dissonant” sounds in the same manner: Start by simply playing the chord and singing the note over top of this harmony. An easy way to do this exercise is to go to the piano. Play the chord and sustain it with the pedal and play the dissonant note on top of it. (Unsure of how to voice a basic chord at the piano? Check out this article.)

Absorb the sound of that note and how it feels in relation to the accompanying chord and then sing it. Once you can confidently sing that note, play it on your instrument along with the chord.

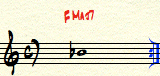

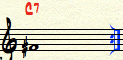

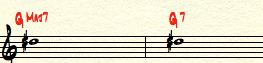

Let’s start out with the 4th scale degree over a Major 7 chord:

Next, do the same for the 4th scale degree on a V7 chord:

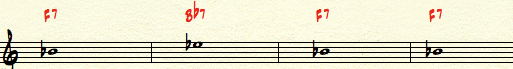

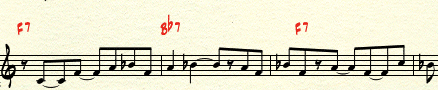

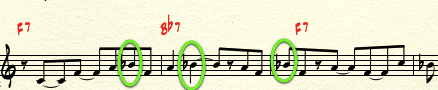

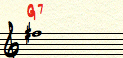

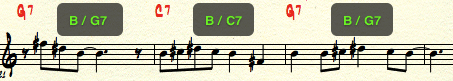

Remember, to get control of these sounds you need to ingrain them into your ear, and the fastest way to do this is through singing. After you can successfully hear, sing, and play the 4th over both a Major 7 and V7 chord, apply this sound to a tune or chord progression that you’re familiar with. The blues is always a good place to start:

You are going to want to resolve down to the third or up to the 5th, but resist the urge. Push through the dissonance until your ear is acclimated to the sound.

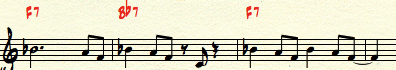

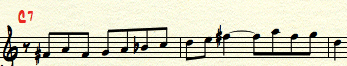

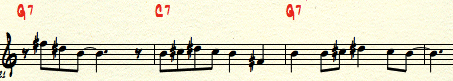

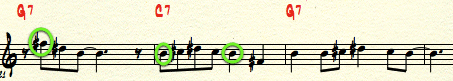

Once you become comfortable hearing that 4th, try creating some simple lines over the blues that utilize the 4th scale degree. In the line below the 4th is emphasized, but the tension is resolved each time:

Another example is Charlie Parker’s tune Relaxin’ at Camarillo:

Notice how Bb, the 4th scale degree of F7, is emphasized in the opening measures of the melody:

It is not merely a passing tone, but a goal note as it lands on strong parts of the beat and is the repeated high point of the melody.

#11 over V7 and Maj.7

While it is one of the more common dissonant notes, many improvisers don’t have the sound of the #11 in their ears. They understand it in theory, and consequently insert it into their solos as a mental exercise rather than a natural part of their line. This is not musical – you can do better.

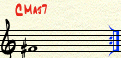

Again, start by familiarizing yourself with this sound and getting it in your ear. Play a major chord at the piano and play and sustain the #11 on top of that chord.

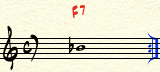

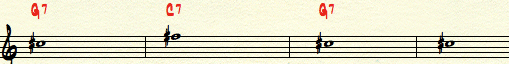

Then play a V7 chord and play the #11 on top:

The result is slightly different with each chord. On the Major 7th chord there is a 4th relationship between the #11 and the major 7th and on the V7 chord there is a major 3rd between the #11 and the b7. Manipulating each of these relationships will create a different effect.

When you can confidently hear and sing the #11 over Major 7 and V7, play that note on your instrument. Again, take a familiar tune or progression like the blues, and apply this note to each chord. Get this unique sound in your ear, to the point that it feels like a different color, not like a mistake:

After you’ve done this preliminary exercise, apply some language that utilizes the #11 over these chords. For example, over a C7 chord you could play this g minor line that emphasizes the #11:

Notice how the top F# is the goal note of the line and is further emphasized by its placement on the downbeats of the second measure:

#5 over Major and V7 / Major 7th over V7

The next “avoid notes,” the #5 and the major 7th over a V7, are a step up in dissonance from the notes we’ve covered so far. Both of these notes are a half-step away from a strong chord tone (the 5th and the 7th). As a result the sound of these notes clashes with the harmonies that we are naturally accustomed to.

Again, go to the piano and sing and play both of these notes to ingrain the sound in your ear. The #5 over Maj.7 and V7 chords:

And the Major 7th scale degree over V7:

Chances are that these less common sounds will be more dissonant to your ear, so spend some extra time on the preliminary exercises hearing, sing, and playing these colors.

For a great example of this dissonance in action, check out how Freddie Hubbard employs both the #5 and major 7th on the tune Birdlike (2:32 in the video):

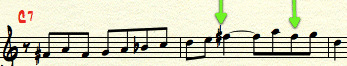

At the beginning of this chorus, Freddie plays this line to create some harmonic tension:

Pay special attention to how he emphasizes the Major 7th scale degree over these V7 chords, a definite “avoid note”:

Now Freddie is not thinking about inserting the major 7th or highlighting the #5, he is clearly thinking B major over G7. In effect utilizing the sound of a slash chord over the first few bars of the blues:

As with the dissonant notes we’ve explored so far, each slash chord also has a varying level of dissonance. For example, slash chords a half-step away from the root (C#/C or F#/G) create more tension while those a whole-step or 5th away from the root are more consonant. In the example above he uses the slash chord a major 3rd above the root (B/G7) and a half-step below the root (B/C7).

When these individual dissonances become more familiar to your ear, start implying entire melodic fragments in different keys on top of these chords in the fashion Freddie uses in the example above.

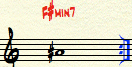

Major 3rd over minor 7

The last dissonant sound we’ll look at is the sound of the major 3rd over a minor 7 chord. This sound is similar to the 4th scale degree over a major or V7 chord in that it is a half-step away from the third of the chord.

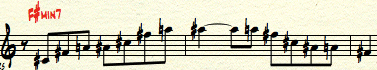

After you’ve ingrained the sound and applied it to a familiar chord progression or tune, start incorporating it into your improvisation. Try a line like the one below, which is essentially an F# minor triad with the addition of the major 3rd:

Simply by inserting that major third into a minor triad or even a minor pentatonic pattern can add interest and tension to that minor 7 chord.

Practicing dissonance

The important point to remember when practicing is to apply these dissonant notes musically. Even the “right notes” sound strange when they are inserted mechanically into a musical line. Think about how a beginner sounds as they try to improvise for the first time, picking random notes from a scale. Without time, rhythm, sound, language, and technique any note, no matter how correct it is, will sound bad.

As shown above, incorporate these concepts into language and lines that you already know. This can be as simple as taking some minor language and applying it to its related V7 chord (as with the G-7 line over C7 to emphasize the #11). Or, you can slightly alter lines, language, and technique that you’ve learned to include these dissonant note choices (as we did above with the F# minor triad).

Keep in mind that the way you hear things is entirely unique to you, dependent upon your listening, practice, and performing experience. Finding the “right notes” in an improvised line is a subjective pursuit based on the experience of your ears. However, contrary to what some people think, this aural perspective does not have to remain set in stone. Over time it should shift and evolve and using the techniques outlined above, your ears can change very quickly.

“You have your way. I have my way. As for the right way, the correct way, and the only way, it does not exist.”~Friedrich Nietzsche

The greatest improvisers can use any note they want in a solo regardless of the chord progression or key of the tune. Listen to Coltrane, McCoy Tyner, Freddie, or Michael Brecker. Harmony for these masters has no limits – Any note over any chord! Think about that.

Once you’ve mastered the elements of musicality, once you’ve explored harmony both aurally and mentally, and when you’re truly playing what you hear, there are no rules. The only barrier is the limit of what you can hear, the limit of what sounds “right” to you. Lucky for you, this doesn’t have to be some far fetched musical fantasy, if you start today, you’ll be there sooner than you think!