Tell me if this scenario sounds familiar:You walk into a jam session ready to play a tune that you’ve been sounding great on. As the band finishes up a set you gather up your courage, walk up to the stage, and call this tune you’ve been working on memorizing all week. But at the last second someone suddenly jumps in and suggests a new tune. All of the sudden you’re up there on the spot with the audience staring at you and this tune that you don’t even know is being counted off.

What key is it in? What is the chord progression? I don’t even know the melody…

You try to play by ear, you try to find a guide tone line, you try desperately to fake it, but nothing works. You go down in flames.

This is bound to happen to every musician at some point because in truth, no one knows every tune. At one point or another, if you’re pushing yourself to get out there and play, you’ll find yourself in a situation just like the one above.

You might be getting together with friends to play some standards and a tune will come up that you don’t know, or you may find yourself in a rehearsal and suddenly you have to solo on a tune in a weird key or chord progression.

In these situations, you’re on the spot and you have to perform something that you’re not comfortable with or worse, totally inexperienced at. It could be a difficult key, a fast tempo, a really slow tempo, Rhythm changes, Moment’s Notice, Giant Steps, the Blues in Db, the lead trumpet part, odd meters, sight reading, transposing…

Whether you realize it or not these experiences are some of the most valuable opportunities you have to improve as an improviser. That’s right, failing – crashing and burning.

Failure is necessary

Failing is a necessary part of the learning process.

Think about it. You’re not going to improve unless you get outside of your comfort zone and take chances, and if you’re taking chances, at some point you’re bound to make a mistake.

Learn to look at failure as a positive thing, it’s a sign that you’re trying something new and striving to getting better. Without pushing yourself forward, you’re going to stay in the same place and stagnate. Tomorrow won’t be that much different from today and next month will pretty much be the same as this month.

By playing it safe you’re staying in the same place musically, day after day after day. You’re not learning new tunes, you’re not expanding your technique, and you’re not learning any new language.

You’ve probably felt like this with improvisation at one point or another. You keep playing the same stuff on the same tunes or maybe you feel like you don’t know what to practice to achieve your goals.

This is a red flag that you’re not taking enough chances musically and that you’re not pushing yourself enough in the practice room. If everything is always comfortable or easy you’re not going to grow. Go to jam sessions, get together to play with other musicians, go see as much live music as you can, and take lessons with the best teachers in your area.

Take a chance and be open to the possibility that you might fail.

Failure is a useful tool. It shows you exactly what you need to work on and gives you the incentive to do it. The momentary humiliation of failure gives you a good source of motivation to get into the practice room and to get to work. You messed up that tune in front of all those people, your fingers didn’t work in the key of C#, you couldn’t hear the melody or chord progression when everyone else could!

Use this experience to learn and grow and to motivate yourself to improve.

You’ve probably heard the story of a young Charlie Parker failing at a jam session and getting a cymbal thrown at his feet mid-solo. This humiliating experience propelled him into the practice room to truly dedicate himself to his craft. This failure gave him the motivation to get serious and showed him exactly what he needed to practice.

The same should be true of you.

Making a choice to improve

To be more accurate, failure by itself is not going to do anything for you – it’s what you do after you fall on your face that counts. When you encounter these situations and you crash and burn on a tune or a solo, you have a choice to make:

#1) You can get discouraged and quit. You can run back home to lick your wounds and you can avoid any experiences like this in the future. “Just going to play it safe from here on out.”

#2) You can blame external sources and act like nothing’s happened. “It’s not my fault I didn’t know that tune. I was going to play the tune I called. Those players were trying to mess me up. That was just an unlucky situation, I don’t need to change anything.“

#3) Or you can take action to improve. Take a look at what went wrong and vow to not fail in the same way again. The next time that tune is called, you’re going to know it. The next time you have to play in the key of B, you’re going to nail it. The next time you solo over rhythm changes it’s going to be better.

If you’re serious about improving there is really only one option to take.

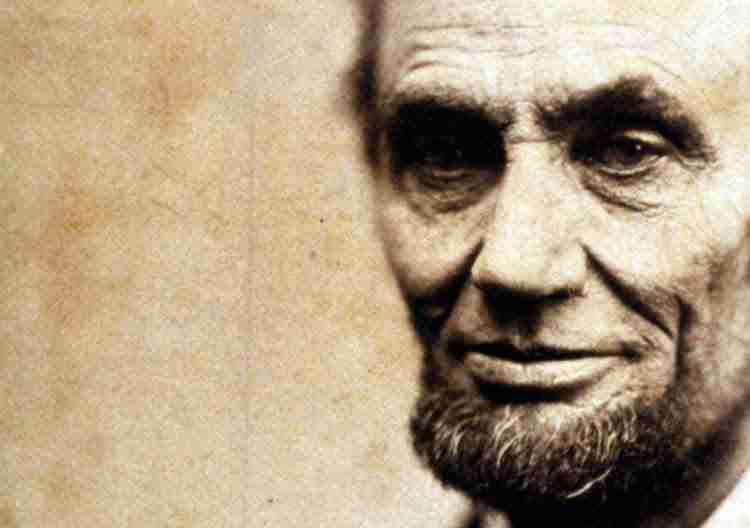

“My great concern is not whether you have failed, but whether you are content with your failure.”~Abraham Lincloln

The next time you’re at a jam session and get caught on stage with a tune you didn’t know, here are the steps you’re going to take to improve:

I) Write it down

When I was in school I would often ask my teachers how to learn more tunes.

Everyday, whether it was in lessons, rehearsals, or informal jam sessions with other students, it seemed like I was always in situations where I didn’t know the tunes being called. One of my teachers finally suggested that I write down the name of any tune that I didn’t know.

So from then on, wherever I was I started taking note of all the tunes that I didn’t know. Simply by paying attention to those unfamiliar tunes, I quickly built up a list of tunes that I was going to learn. In the space of a few weeks I knew exactly what I needed to work on.

When you don’t know a lot of tunes, the prospect of building a repertoire can seem staggeringly overwhelming. Trying to take on hundreds of tunes at once leads to inertia. However when you take one tune at a time, you’ll slowly build up a good base of tunes without feeling stressed or overwhelmed.

The next time you find yourself at a jam session and you don’t know a tune, write it down, make a note in your phone, get a pen and write it on your hand – whatever it takes. Remember this moment and remember the name of the tune or the technique that you need to work on.

If you don’t make a note of it, you’re not going to learn it. Weeks and months will go by where you’re not learning any new tunes. If you don’t make a change this same situation is going to happen again and again.

Make it your goal to not fail at the same tune twice.

II) Find a recording of the tune

Now that you have an objective, it’s time to get to know this “unknown” tune as well as you can. It all begins with listening.

This process is easy and even fun. With resources like YouTube, Spotify, and many others you pretty much have every recording that you’d ever need to find right at your finger tips.

Checking out recordings is something that you can do anywhere, you don’t have to be stuck in a practice room to get a melody and chord progression in your ears.

When you get caught with a tune that you don’t know find the player that made this tune famous, find the landmark recording of the tune, and find your favorite player interpreting this tune.

In the past I used to make playlists for a tune I was trying to learn, 8-10 tracks of different players playing the same tune spanning the spectrum from early to modern improvisers and styles.

As you listen, sing the tune and if there are lyrics make sure you learn the words.

III) Learn the melody by ear

Now comes the melody.

If you can sing the melody, you can figure it out by ear. Learn the melody phrase by phrase from the recording.

At this point you may find yourself wanting to run to the real book to look up the melody. You can have the answer right there on the page, but the truth is this isn’t going to help you in the long run. If you’re having trouble hearing the intervals of a melody on the bandstand, it means that you need to do some ear training work in the practice room.

The one thing that can save you from crashing and burning are your ears and if you’re reading out of the real book to learn or perform a tune, you’re ignoring your ears. When you learn how to hear intervals, melodies, and the sound of different chords you’ll have a set of skills to rely on when you’re caught off guard. This is why ear training is so important for the improviser.

When it comes to learning a melody by ear, it’s a three step process: Listen to a melodic phrase, sing it, then figure it out on your instrument. That’s it, and the more you do it the easier it will get.

IV) Learn the chord progression by ear

When you’re trying to learn a tune the melody is only part of the process, you also need to learn the chord progression. Just like the melody, you’ll be much more successful learning the changes by ear.

Check out this article on how to hear chord changes.

V) Transcribe part of a solo on the tune

Maybe the trouble with the tune wasn’t the melody or chord progression, but the fact that you had trouble soloing over it.

You got lost in the form, you had nothing to play over the bridge, you were using the same old licks in the same places… You need some inspiration, some new ideas, and a new approach. When you find yourself in this situation, imitating a great model will inspire you to find your own voice. This means that you need to start transcribing language.

Check out your favorite players soloing over this tune and then pick a line or phrase that grabs your ear. Now learn that musical line from the record – figure out the notes, imitate the sound, copy the articulation, memorize it, and then learn it in all 12 keys. With this approach, sometimes one solo can be enough to change your playing.

VI) Call the tune at the next jam session

Now you’ve come full circle. This tune that you crashed and burned on is now a tune that you own, one that you would feel confident performing in front of an audience.

The last step is calling this tune at a jam session or even the next time you get together to play with some friends. Make this tune a usable part of your repertoire.

The process is the same for any tune that you don’t know or any tune that you fail on. The more tunes that you learn in this way, the easier this process will become and the better that your ears get. Eventually you’ll be able to learn melodies and chord progressions very quickly and even hear them on the fly. This is the goal for any aspiring improviser.

Remember, every time that you fall on your face in front of an audience is a chance to make a change and to improve your musical abilities. Don’t just give up and don’t try to forget about the experience, use it to bring yourself closer to your goals.

Everybody fails at one point or another, but not everyone gets back on stage and pushes themselves to get better. Make sure you do.